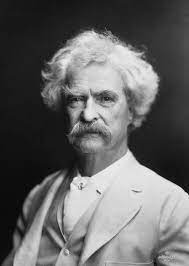

Mark Twain visited Hobart on 2 November 1895.

He wrote about Hobart. His words live on.

“The voyage up the Derwent Firth displays a grand succession of fairy visions, in its entire length elsewhere unequalled. In gliding over the deep blue sea studded with lovely isles luxuriant to the water’s edge, one is at a loss which scene to choose for contemplation and to admire most. When the Huon and Bruni have been passed, there seems no possible chance of a rival; but suddenly mount Wellington, massive and noble like his brother Etna, literally heaves in sight, sternly guarded on either hand by Mounts Nelson and Rumney; presently we arrive at Sullivan’s Cove – Hobart!

It is an attractive town. It sits on low hills that slope to the harbour – a harbour that looks like a river and is as smooth as one. Its still surface is pictured with dainty reflections of boats and grassy banks and luxuriant foliage. Back of the town rise highlands that are clothed in woodland loveliness, and over the way is that noble mountain, Wellington, a stately bulk, a most majestic pile. How beautiful is the whole region, for form, and grouping, and opulence, and freshness of foliage, and variety of color, and grace and shapeliness of the hills, the capes, the promontories; and then, the splendour of the sunlight, the dim rich distances, the charm of the water-glimpses! And it was in this paradise that the yellow-liveried convicts were landed, and the Corps–bandits quartered, and wanton slaughter of the kangaroo-chasing black innocents consummated on that autumn day in May, in the brutish old time. It was all out of keeping with the place, a sort of bringing of heaven and hell together.

However that maybe, its supremacy in neatness is not to be questioned. There cannot be another town in the world that has no shabby exteriors; no rickety gates and fences, no neglected houses crumbling to ruin, no crazy and unsightly sheds, no weed-grown front yards of the poor, no backyards littered with tin cans and old boots and empty bottles, no rubbish in the gutters, no clutter on the sidewalks, no outer-borders fraying out into dirty lanes and tin-patched huts. No, in Hobart all the aspects are tidy, and all a comfort to the eye; the modestest cottage looks combed and brushed and has its vines, its flowers, its neat fence, its neat gate, its comely cat asleep on the window ledge.

We had a glimpse of the museum, by courtesy of the American gentleman who is the curator of it. It has samples of half-a-dozen different kinds of marsupials. (A marsupial is a plantigrade vertebrate whose speciality is its pocket. In some countries it is extinct, in others it is rare. The first American marsupials were Stephen Girard, Mr. Aston and the opossum; the principal marsupials of the Southern Hemisphere are Mr. Rhodes, and the kangaroo. I, myself, am the latest marsupial. Also, I might boast that I have the largest pocket of them all. But there is nothing in that.)”

He wrote about Hobart. His words live on.

“The voyage up the Derwent Firth displays a grand succession of fairy visions, in its entire length elsewhere unequalled. In gliding over the deep blue sea studded with lovely isles luxuriant to the water’s edge, one is at a loss which scene to choose for contemplation and to admire most. When the Huon and Bruni have been passed, there seems no possible chance of a rival; but suddenly mount Wellington, massive and noble like his brother Etna, literally heaves in sight, sternly guarded on either hand by Mounts Nelson and Rumney; presently we arrive at Sullivan’s Cove – Hobart!

It is an attractive town. It sits on low hills that slope to the harbour – a harbour that looks like a river and is as smooth as one. Its still surface is pictured with dainty reflections of boats and grassy banks and luxuriant foliage. Back of the town rise highlands that are clothed in woodland loveliness, and over the way is that noble mountain, Wellington, a stately bulk, a most majestic pile. How beautiful is the whole region, for form, and grouping, and opulence, and freshness of foliage, and variety of color, and grace and shapeliness of the hills, the capes, the promontories; and then, the splendour of the sunlight, the dim rich distances, the charm of the water-glimpses! And it was in this paradise that the yellow-liveried convicts were landed, and the Corps–bandits quartered, and wanton slaughter of the kangaroo-chasing black innocents consummated on that autumn day in May, in the brutish old time. It was all out of keeping with the place, a sort of bringing of heaven and hell together.

However that maybe, its supremacy in neatness is not to be questioned. There cannot be another town in the world that has no shabby exteriors; no rickety gates and fences, no neglected houses crumbling to ruin, no crazy and unsightly sheds, no weed-grown front yards of the poor, no backyards littered with tin cans and old boots and empty bottles, no rubbish in the gutters, no clutter on the sidewalks, no outer-borders fraying out into dirty lanes and tin-patched huts. No, in Hobart all the aspects are tidy, and all a comfort to the eye; the modestest cottage looks combed and brushed and has its vines, its flowers, its neat fence, its neat gate, its comely cat asleep on the window ledge.

We had a glimpse of the museum, by courtesy of the American gentleman who is the curator of it. It has samples of half-a-dozen different kinds of marsupials. (A marsupial is a plantigrade vertebrate whose speciality is its pocket. In some countries it is extinct, in others it is rare. The first American marsupials were Stephen Girard, Mr. Aston and the opossum; the principal marsupials of the Southern Hemisphere are Mr. Rhodes, and the kangaroo. I, myself, am the latest marsupial. Also, I might boast that I have the largest pocket of them all. But there is nothing in that.)”