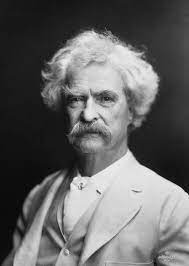

Mark Twain arrived in Hobart on the 2 November 1895.

After Hobart he departed for New Zealand.

Part three of an article was published in a local newspaper: Tasmanian News.

There was another silence here. Mark Twain is eminently companionable. Presently he began inconsequently,

“Ah, those maps! What erroneous ideas they give one! Before I came over on this tour I’d seen Australia and New Zealand on the maps. Glancing at the map I had an idea that there was probably a small ferry boat running eighteen or twenty times a day between Melbourne and New Zealand. When I came to inquire about the name of the ferry boat, it was taken as the remark of and ignorant person. That’s the trouble with maps: they get a lot of stuff into a small space, and give one and inadequate idea of distance. There was an old lady ran out the gate to me once in Bermuda-came bounding out of the gate and said, ’That’s your ship lying in the offing there? An American ship? You belong in America?’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I belong in America.’ ‘Ahh,’ she said, ‘I’ve got a nephew there- a journeyman carpenter- and he works down in the lower part of New York City. His name’s J M White: Perhaps you’ve met him? And she wanted me to hunt him up. Now that looks silly, but coming from a person who’s only looked at a map it was perfectly natural.”

“You’re going to India, Mr Clemens. Been there before?”

“Never. But I have received the pleasantest kind of letters from people connected with the civil and military administrations in India for years past. I shall people in India whom I have not previously met, but who are still my friends.”

“As you do everywhere?”

“Well, yes, as I do everywhere, since you are kind enough to put it so. A book? Why, on such a trip as this, one could write a library of books! If I do subsequently write a book, it will be an incident consequent on the tour rather than any attempt at dealing with the tour itself. Of course, on a lecturing tour one has to combine business with pleasure, and I can’t say that they harmonize very well. Then I have had a succession of carbuncles- have one, just about spent, on my leg now- and they keep me rather lame. The only good times I have had- times, that is to say, when I have been entirely free of pain- have been on the platform, talking to my audiences. At such a time ones’ mind is fully occupied, and one has not attention to waste on pain. Yes, I naturally look forward to my visit to the East with anticipation more than ordinarily pleasurable, although I’ve only heard positively of one Asiatic who took what I may call a literary interest in me. He was a Chinaman, and a friend of mine who was American Consul at Singapore recommended him to read my New Pilgrim’s Progress, venturing to praise the book as interesting and funny. The Chinaman got a book, written in his own language and illustrated with quaintly forcible woodcuts of fights with Apollyon, Christian’s experiences in the valley of the Shadow of Death, and that sort of thing: it was the original Pilgrim’s Progress, published sometime ahead of mine, and differing in tone and treatment. The Chinaman read it, and seeking my friend the Consul (one cannot account for the literary tastes of the Chinese) protested in a pained manner, as one who would deprecate a practical joke, that there was not a funny joke in the book from one end to the other. The Consul...”

But at this moment Mr Clemens was appropriated by a local gentleman with fossils to exhibit, and after a brief leave-taking I saw him no more…

After Hobart he departed for New Zealand.

Part three of an article was published in a local newspaper: Tasmanian News.

There was another silence here. Mark Twain is eminently companionable. Presently he began inconsequently,

“Ah, those maps! What erroneous ideas they give one! Before I came over on this tour I’d seen Australia and New Zealand on the maps. Glancing at the map I had an idea that there was probably a small ferry boat running eighteen or twenty times a day between Melbourne and New Zealand. When I came to inquire about the name of the ferry boat, it was taken as the remark of and ignorant person. That’s the trouble with maps: they get a lot of stuff into a small space, and give one and inadequate idea of distance. There was an old lady ran out the gate to me once in Bermuda-came bounding out of the gate and said, ’That’s your ship lying in the offing there? An American ship? You belong in America?’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I belong in America.’ ‘Ahh,’ she said, ‘I’ve got a nephew there- a journeyman carpenter- and he works down in the lower part of New York City. His name’s J M White: Perhaps you’ve met him? And she wanted me to hunt him up. Now that looks silly, but coming from a person who’s only looked at a map it was perfectly natural.”

“You’re going to India, Mr Clemens. Been there before?”

“Never. But I have received the pleasantest kind of letters from people connected with the civil and military administrations in India for years past. I shall people in India whom I have not previously met, but who are still my friends.”

“As you do everywhere?”

“Well, yes, as I do everywhere, since you are kind enough to put it so. A book? Why, on such a trip as this, one could write a library of books! If I do subsequently write a book, it will be an incident consequent on the tour rather than any attempt at dealing with the tour itself. Of course, on a lecturing tour one has to combine business with pleasure, and I can’t say that they harmonize very well. Then I have had a succession of carbuncles- have one, just about spent, on my leg now- and they keep me rather lame. The only good times I have had- times, that is to say, when I have been entirely free of pain- have been on the platform, talking to my audiences. At such a time ones’ mind is fully occupied, and one has not attention to waste on pain. Yes, I naturally look forward to my visit to the East with anticipation more than ordinarily pleasurable, although I’ve only heard positively of one Asiatic who took what I may call a literary interest in me. He was a Chinaman, and a friend of mine who was American Consul at Singapore recommended him to read my New Pilgrim’s Progress, venturing to praise the book as interesting and funny. The Chinaman got a book, written in his own language and illustrated with quaintly forcible woodcuts of fights with Apollyon, Christian’s experiences in the valley of the Shadow of Death, and that sort of thing: it was the original Pilgrim’s Progress, published sometime ahead of mine, and differing in tone and treatment. The Chinaman read it, and seeking my friend the Consul (one cannot account for the literary tastes of the Chinese) protested in a pained manner, as one who would deprecate a practical joke, that there was not a funny joke in the book from one end to the other. The Consul...”

But at this moment Mr Clemens was appropriated by a local gentleman with fossils to exhibit, and after a brief leave-taking I saw him no more…